BENEATH THE SURFACE OF BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN

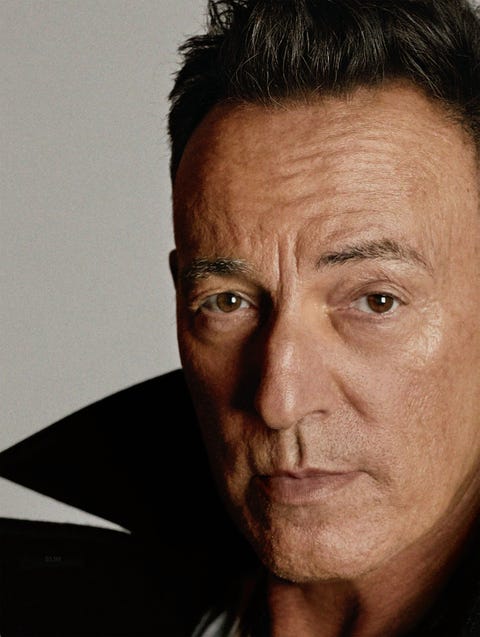

he first time I meet Bruce Springsteen is backstage at the Walter Kerr Theatre in New York, where he is in the homestretch of performing his one-man show, Springsteen on Broadway. It is a few weeks before I am supposed to sit with him for an interview, but his publicist has asked me to come by before this performance so he can, I deduce, check me out. I arrive at 7:00 and am directed to a small couch near the backstage bathroom. Finally, five minutes before curtain, I see, coming down the stairs that lead to his dressing room, a pair of black work boots and black-legged jeans. Springsteen ducks his head beneath a low arch and walks toward me, extending his hand and saying, “I’m Bruce.” We shake hands, and then there is silence. He looks at me and I look at him, not sure what to say. At five-foot-ten, he’s taller than you think he’ll be; somehow, he remains the runty-scrawny kid in the leather jacket, possibly dwarfed in our minds due to the years he spent leaning against Clarence Clemons.

That evening, Springsteen is weeks from notching his sixty-ninth birthday. And as we stand there, I find it impossible not to think that the journey he has undertaken in this decade of his life has been nothing short of miraculous. He entered his sixties struggling to survive a crippling depression, and now here he is approaching his seventies in triumph—mostly thanks to the success of this powerful, intimate show, which is not a concert but an epic dramatic monologue, punctuated with his songs. After a year of sold-out shows, he will close it out on December 15, the same night it will debut on Netflix as a film. He at last breaks the awkward silence by giving a small nod and saying to me—but more to himself, just as we all kind of say it to ourselves as we head out the door each day—“Well, I guess I better go to work.” And with that he ambles toward stage right.

NA.”

This is, curiously, the first word that Springsteen says when he takes the stage. An unlikely, unromantic, unpoetic choice for a man who has always been more about the sensory than science. Yet in many ways, DNA is Springsteen’s unrelenting antagonist, the costar that he battles against. This is the central tension of Springsteen on Broadway: the self we feel doomed to be through blood and family versus the self we can—if we have the courage and desire—will into existence. Springsteen, as he reveals here, has spent his entire life wrestling with that question that haunts so many of us: Will I be confined by my DNA, or will I define who I am?

A few minutes later, in the show, he talks about the moment that opened his eyes to what was possible if one believed in the power of self-creation. It’s a Sunday night in 1956, and an almost seven-year-old Springsteen is sitting in front of the TV with his mother, Adele, in the living room of the tiny four-room house in Freehold, New Jersey, that he shares with his parents and sister. This is the night he sees Elvis Presley. In that moment, when he receives that vision, he realizes that there is another way, that he can create an identity apart from “the lifeless, sucking black hole” that is his childhood.

“All you needed to do,” Springsteen says when he unpacks the lesson Elvis taught him, “was to risk being your true self.”

“Yeah. . .,” Springsteen says when I sit down with him a couple weeks later and tell him it seems the essential question of his show is “Are we bound by what courses through our veins?” He looks off to his left into his dressing-room mirror, the surface of which is checkerboarded with photographs, much as a mirror in a teenage boy’s bedroom might be. Among the many images: John Lennon in his NEW YORK CITY T-shirt. A young Paul McCartney. Patti Smith. Johnny Cash. They are, as Springsteen tells me later, “the ancestors.” It’s into this mirror and toward these talismans that Springsteen often gazes when he is answering my questions. He’s a deep listener and acts with intent. He has a calm nature and possesses a low, soft voice. He has a tendency to be self-deprecating, preemptively labeling certain thoughts “corny.” He smiles easily and likes to sip ginger ale. Sometimes before telling you something personal, he lets out a short, nervous laugh. Above all, he speaks with the unveiledness of a man who has spent more than three decades undergoing analysis—and credits it with saving his life.

His cramped dressing room looks more like the “office” the superintendent of your prewar apartment building carves out for himself in the basement, next to the boiler. Much of it feels scavenged. There’s a brown leather couch and a beat-up coffee table. Nailed up above the couch is a faded, forty-eight-star American flag and a ragged strand of white Christmas-tree lights. Now Springsteen sits on the couch before me, dressed in black jeans and a white V-neck T-shirt that reveals a faint scar at the base of his neck—the scar that remains from a few years ago, when surgeons cut him open to repair deterioration on some cervical discs in his neck that had been causing numbness on the left side of his body. On his right ring finger is a gold ring in the shape of a horseshoe.

Finally, he speaks.

“DNA is a big part of what the show is about: turning yourself into a free agent. Or, as much as you can, into an adult, for lack of a better word. It’s a coming-of-age story, and I want to show how this—one’s coming of age—has to be earned. It’s not given to anyone. It takes a certain single-minded purpose. It takes self-awareness, a desire to go there. And a willingness to confront all the very fearsome and dangerous elements of your life—your past, your history—that you need to confront to become as much of a free agent as you can. This is what the show is about...It’s me reciting my ‘Song of Myself.’ ”

But as you learn after spending time with him, there is what is on the surface and then there is what is below. Because the show is also about other tensions: solitude versus love (the ability to give it as well as receive it); the psychological versus the spiritual; the death force versus the life force; and, most of all, the father versus the son. Yes, it is about his struggle to find his true self, his identity. But most of all, it is about his father—and Springsteen’s search to find peace with the man who created him but, in many ways, almost destroyed him. Here’s Springsteen describing in his 2016 autobiography, Born to Run, how he saw himself as a young boy, and how his father perceived him:

Weirdo sissy-boy. Outcast. Alienated. Alienating. Shy. Soft-hearted dreamer. A forever-doubting mind. The playground loneliness . . . “[I had] a gentleness, a timidity, shyness, and a dreamy insecurity. These were all the things I wore on the outside and the reflection of these qualities in his boy repelled [my father]. It made him angry.”

He tells me his father made him ashamed that he was not hard like him but more like his mother. “My mother was kind and compassionate and very considerate of others’ feelings. She trod through the world with purpose, but softly, lightly. All those were the things that aligned with my own spirit. That was who I was. They came naturally to me. My father looked at all those things as weaknesses. He was very dismissive of primarily who I was. And that sends you off on a lifelong quest to sort through that.”

Comments

Post a Comment